HIT 4Ts Score Calculator

The 4Ts score is a clinical prediction tool used to assess the probability of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT). It helps determine if further laboratory testing is needed. The score ranges from 0-8, with higher scores indicating greater likelihood of HIT.

Based on information from the article, scores of 0-3 indicate low probability, 4-5 indicate intermediate probability, and 6-8 indicate high probability of HIT.

Based on your score:

Next steps:

Consult your healthcare provider for further evaluation.

What Is Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia?

Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia is a rare but life-threatening reaction to heparin, a common blood thinner used to prevent clots. Despite its name, this condition doesn’t cause bleeding-it makes your blood more likely to clot dangerously. It happens when your immune system mistakenly attacks a complex formed by heparin and a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4). This triggers platelets to clump together and get destroyed, dropping your platelet count. But here’s the twist: while your platelets fall, your body starts forming clots in veins and arteries.

This isn’t just a lab anomaly. About half of people who develop HIT will also get a blood clot-deep vein thrombosis in the leg, a pulmonary embolism in the lung, or even a stroke. Without quick action, up to 30% of these cases can be fatal.

Two Types of HIT-Only One Is Dangerous

Not all drops in platelets after heparin are the same. There are two types:

- Type I (HAT): Mild, harmless, and temporary. Platelets dip slightly within the first 1-2 days after starting heparin, then bounce back on their own. No treatment needed.

- Type II (HIT): The real threat. This is immune-driven. It shows up 5 to 14 days after starting heparin-or as fast as 1 to 3 days if you’ve had heparin in the last 100 days. This is the form that causes clots, skin damage, and organ failure.

Only Type II is called HIT. It’s what doctors panic about. And it’s why you can’t ignore a platelet drop after day 4 of heparin therapy.

Who’s at Risk?

Not everyone gets HIT. But some people are far more likely to.

- Women have 1.5 to 2 times higher risk than men.

- People over 40 are 2 to 3 times more likely to develop it than younger adults.

- Orthopedic surgery patients-especially after hip or knee replacements-are at highest risk, with up to 10% developing HIT.

- Unfractionated heparin carries a 3-5% risk. Low molecular weight heparin (like enoxaparin) is safer, but still causes HIT in 1-2% of users.

- Duration matters. Less than 5 days of heparin? Risk is under 0.5%. Between 5 and 10 days? Risk jumps to 3-5%. Beyond 10 days? It hits 5-10%.

- Re-exposure within 100 days can trigger HIT in just 24-72 hours. If you had HIT before, you’re at serious risk again.

That’s why hospitals monitor platelet counts closely in surgical patients on heparin-especially after day 4.

What Are the Warning Signs?

HIT doesn’t always scream for attention. But when it does, here’s what to look for:

- Swelling, warmth, or pain in one leg-signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). This happens in 25-30% of HIT cases.

- Sudden shortness of breath or chest pain-possible pulmonary embolism (PE). Seen in 15-20% of cases.

- Dark, bruised, or blackened skin around injection sites. This isn’t just a rash-it’s skin necrosis. Occurs in 10-15% of severe cases.

- Blue or cold fingers, toes, nose, or nipples-signs of acral ischemia. A red flag for widespread clotting.

- Fever, chills, dizziness, or anxiety-often overlooked, but common.

One patient described it like this: "I felt my calf get hot and tight. Then my chest started crushing. I thought I was having a heart attack. But it was my blood turning to stone."

How Is HIT Diagnosed?

There’s no single blood test that gives a yes or no. Diagnosis is a two-step puzzle.

First, doctors use the 4Ts score:

| Category | Score 0 | Score 1 | Score 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombocytopenia | Platelets >150,000 or drop <50% | Platelets 100,000-150,000 or drop 30-50% | Platelets <100,000 or drop >50% |

| Timing | Platelet drop outside 5-14 days | Platelet drop 5-14 days after heparin start | Platelet drop 1-4 days after recent heparin exposure |

| Thrombosis | No new clot | Existing clot only | New or worsening clot |

| Other causes | Clear alternative cause | Possible other cause | No other explanation |

A score of 6-8 means high probability. 4-5 is intermediate. 0-3 is low. Only if the score is high or intermediate do doctors order lab tests.

Then come the lab tests:

- Immunoassay (ELISA): Detects antibodies against PF4-heparin. Very sensitive-95-98%-but can give false positives.

- Functional assay (SRA or HIPA): The gold standard. Checks if antibodies actually activate platelets. 99% specific. Takes days, but confirms HIT.

Even with perfect testing, 1 in 1,000 patients with HIT will be missed. That’s why clinical judgment matters as much as the numbers.

What Happens If HIT Is Left Untreated?

Ignoring HIT is like ignoring a ticking bomb.

Without treatment, 50% of patients develop new clots. Of those:

- 5-10% lose a limb to gangrene

- 20-30% die

Even if you survive, you might need lifelong anticoagulation. Or you might develop post-thrombotic syndrome-chronic leg pain, swelling, and ulcers.

And here’s another danger: if you start warfarin (Coumadin) too early, it can cause warfarin-induced skin necrosis. The skin turns black, dies, and falls off. That’s why warfarin is never started until platelets recover above 150,000 and you’re already on a safe alternative.

How Is HIT Treated?

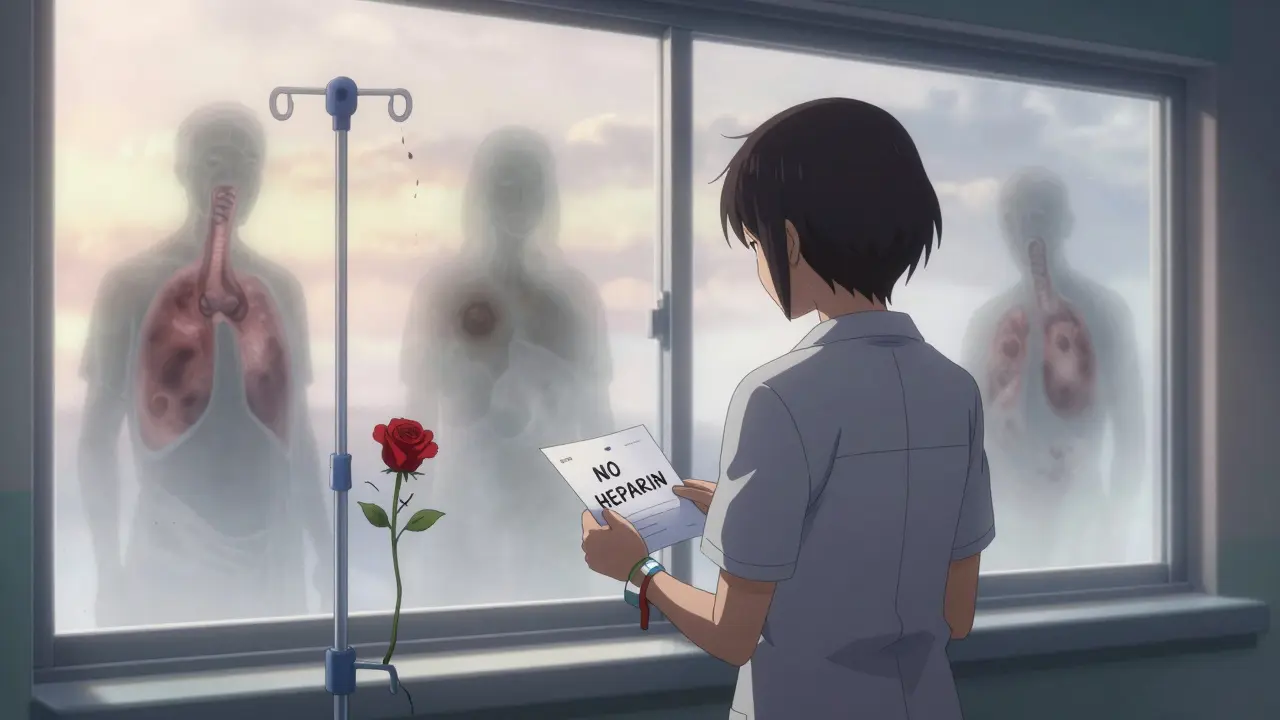

There’s only one rule: Stop all heparin immediately. That includes flushes, heparin-coated catheters, even heparin lock solutions.

Then start a non-heparin anticoagulant right away. The choices:

- Argatroban: Given through IV. Used if you have liver problems. Dose: 2 mcg/kg/min, adjusted by blood test.

- Bivalirudin: Preferred in heart surgery patients. Given IV.

- Fondaparinux: A once-daily shot. Now recommended as first-line for non-critical HIT. 92% effective.

- Danaparoid: Available in some countries. Not in the U.S.

These drugs don’t trigger the same immune reaction. They block clotting without touching PF4.

Once platelets recover and the acute danger passes, doctors may switch to warfarin-but only after at least 5 days of the alternative drug and platelets above 150,000.

How long do you stay on anticoagulants?

- Isolated HIT (no clot): 1-3 months

- HIT with clot (HITT): 3-6 months

- Repeated clots: lifelong

What Should You Do If You’re on Heparin?

If you’re receiving heparin-whether in hospital or at home-here’s what you need to know:

- Ask: "Am I at risk for HIT?" Especially if you’re over 40, female, or had surgery.

- Know the signs: sudden leg pain, chest tightness, skin darkening.

- Ask for platelet counts every 2-3 days between days 4 and 14.

- If your platelets drop more than 50%, demand a 4Ts score.

- Never assume a drop is "just a side effect." It might be HIT.

Many patients don’t realize they’re at risk. One woman in Alberta had a knee replacement, got heparin, and didn’t think twice-until her calf swelled and her skin turned purple. She almost lost her leg.

What’s New in HIT Research?

Science is catching up.

New tests are being developed to detect antibodies that bind only to PF4-without heparin. These could cut false positives from 15% down to 5%.

Fondaparinux is now the preferred first choice in many guidelines because it’s easy to use, doesn’t need blood tests, and works as well as IV drugs.

And researchers are working on entirely new anticoagulants that don’t interact with PF4 at all. Two are in Phase II trials. If they work, HIT might become a footnote in medical history.

But for now, the best defense is awareness. Heparin saves lives. But it can also steal them-if you don’t know the warning signs.

Living With a History of HIT

If you’ve had HIT, you’re not just a patient-you’re someone who survived a hidden danger.

You’ll need to tell every doctor, dentist, and surgeon about it. Even a small heparin flush during a dental procedure could trigger a recurrence.

Carry a medical alert card. Wear a bracelet. Make sure your family knows what HIT is.

And if you need anticoagulation again? You’ll need alternatives: direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) like rivaroxaban or apixaban are generally safe. But never, ever go back to heparin.

The fear of recurrence is real. Eighty percent of survivors say they worry about future procedures. That’s normal. But with the right knowledge, you can live safely.