Most people with diabetes assume that if they have a reaction at the injection site, it’s just irritation or a bad needle. But sometimes, it’s something more serious: an insulin allergy. It’s rare-only about 2.1% of insulin users experience it-but when it happens, it can be dangerous if ignored. The good news? Most cases are manageable with the right steps. You don’t have to stop insulin. You don’t have to panic. You just need to know what to look for and what to do next.

What Does an Insulin Allergy Actually Look Like?

Not every red bump or itchy spot means you’re allergic. Many people mistake normal injection site irritation for an allergy. True insulin allergies are immune system responses-your body sees insulin or one of its additives as a threat. There are three main types of reactions, and they show up differently.Localized reactions are the most common. You’ll notice swelling, redness, and itching right where you injected. Sometimes, a hard lump forms under the skin within 30 minutes to 6 hours. These lumps can be tender and last a day or two. About 85% of these go away on their own. But if they keep coming back, or if they get worse, it’s not just irritation-it’s your immune system reacting.

Systemic reactions are rare but serious. These affect your whole body. Think hives, swelling of the lips or throat, trouble breathing, dizziness, or a sudden drop in blood pressure. These can start within minutes of injecting. If you feel any of these, call emergency services immediately. This isn’t something to wait out. Anaphylaxis can happen fast.

Delayed reactions are the trickiest. You might have used insulin for years without issues, then suddenly, after 10 or 15 years, your joints start aching, or your skin bruises easily at injection sites. These can show up 2 to 24 hours after the shot. Unlike immediate reactions, these are driven by T-cells, not IgE antibodies. That means antihistamines won’t help much. Instead, you need topical treatments like tacrolimus or corticosteroid creams.

Is It the Insulin-or the Additives?

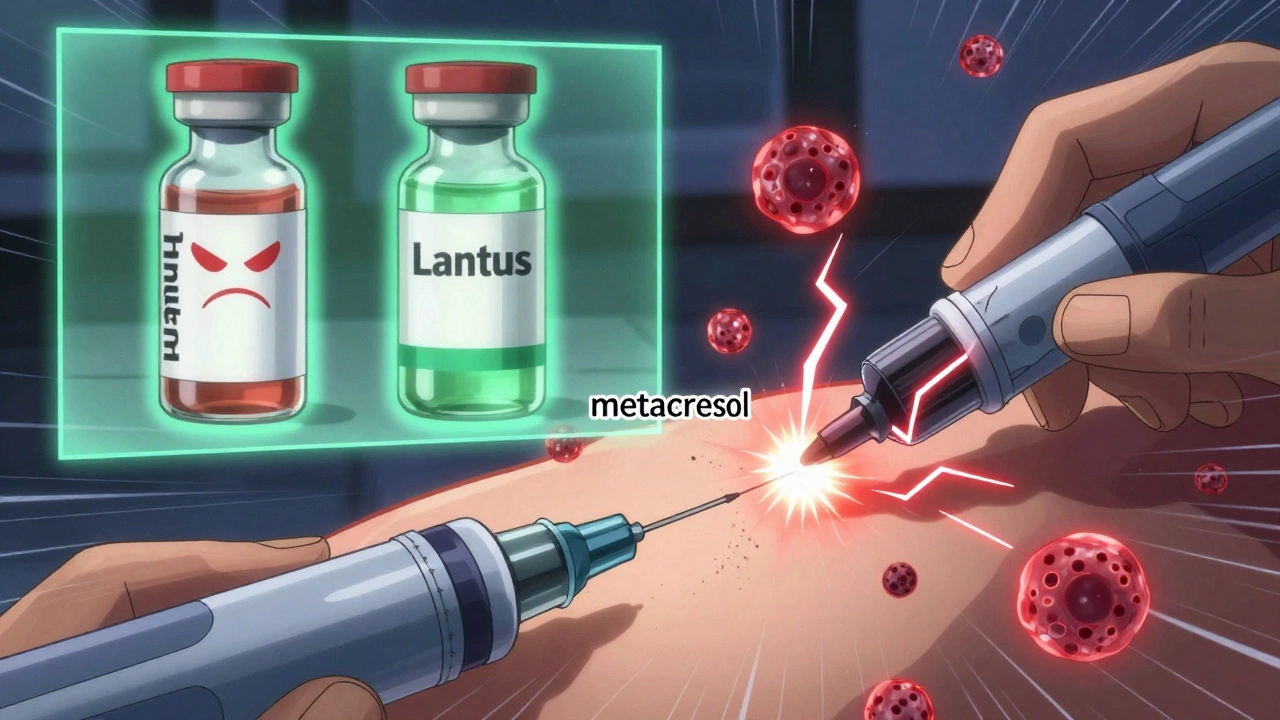

You might think the insulin molecule itself is the problem. But often, it’s not. Many insulin products contain preservatives and stabilizers like metacresol and zinc. These additives can trigger reactions, especially in people with sensitive skin or existing allergies.For example, Humalog has higher levels of metacresol than other insulins. If you’re reacting to Humalog but not to Lantus or NovoLog, it’s likely not the insulin-it’s the preservative. Switching brands can sometimes solve the problem without needing complex treatments.

That’s why allergists and diabetes specialists work together. They test not just for insulin antibodies, but for reactions to excipients. Skin prick tests and blood tests for specific IgE antibodies can pinpoint whether it’s the insulin, the preservative, or even the injection device causing the issue.

What to Do When You Suspect an Allergy

Don’t stop taking insulin. That’s the biggest mistake people make. Stopping insulin-even for a day-can lead to diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening condition. Instead, take these steps:- Document everything. Write down the date, time, insulin type, dose, injection site, and symptoms. Note how long they lasted and what helped (if anything).

- Take a photo of the reaction. Skin changes can fade quickly. A photo gives your doctor a clear record.

- Call your diabetes care team. Don’t wait. They’ll refer you to an allergist if needed.

- Don’t try to self-diagnose. Sweating, shaking, or anxiety after an injection? That’s low blood sugar-not an allergy. Know the difference.

For mild, localized reactions, over-the-counter antihistamines like cetirizine or loratadine can help with itching and swelling. Topical hydrocortisone cream applied right after the shot may reduce inflammation. But if the reaction keeps happening, you need more than creams and pills.

Treatment Options That Actually Work

There are three proven paths when a true insulin allergy is confirmed:1. Switch insulin types - This works for about 70% of people. Try moving from animal-derived to human insulin, or from one analog to another. If you’re on Humalog, try NovoRapid. If you’re on Lantus, try Basaglar. Many patients find relief just by changing the brand or formulation.

2. Use topical immunosuppressants - For delayed reactions, dermatologists recommend applying tacrolimus (Protopic) or pimecrolimus (Elidel) to the injection site immediately after injecting, then again 4 to 6 hours later. These creams calm T-cell responses without weakening your whole immune system. Some doctors also prescribe mid-to-high potency steroid creams like flunisolide 0.05% for short-term use.

3. Insulin desensitization - This is for people who can’t switch insulin or whose reactions are severe. Under medical supervision, you get tiny, increasing doses of insulin over hours or days. The goal is to train your immune system to stop reacting. Studies show this works completely in about two-thirds of cases and helps the rest. It’s not quick, and it’s not done at home-but it can save your life.

For the small number of people who don’t respond to any of these, oral diabetes medications may be an option-but only if you have type 2 diabetes. Type 1 patients must stay on insulin. There’s no alternative.

When to Call 999 (or 911)

Not every reaction needs an ambulance. But if you experience any of these, don’t wait. Don’t drive yourself. Call emergency services right away:- Swelling of the lips, tongue, or throat

- Wheezing or difficulty breathing

- Feeling faint, dizzy, or confused

- Rapid heartbeat or skin turning blue or pale

- A sudden drop in blood pressure

These are signs of anaphylaxis. Epinephrine is the only treatment that can stop it. If you’ve had a systemic reaction before, your doctor should prescribe an epinephrine auto-injector and teach you how to use it. Keep it with you at all times.

Why Consistent Insulin Use Matters

You might think skipping doses will help your body “cool down.” But that’s not true. The Independent Diabetes Trust warns that inconsistent insulin use can make allergic reactions worse-or bring them back after they seemed gone. Your immune system doesn’t forget. It remembers. And when you reintroduce insulin after a break, it may react even more strongly.That’s why doctors stress continuity. Even if you’re having reactions, keep taking insulin as prescribed-while you work with your team to fix the problem. Stopping insulin is riskier than managing the allergy.

What’s Changing in Insulin Allergy Care

Newer insulin formulations are being designed with fewer immunogenic additives. Companies are testing alternative preservatives and delivery systems to reduce reactions. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are also helping doctors safely run desensitization protocols by catching early signs of hypoglycemia during the process.Researchers are also looking for biomarkers-biological signs that predict who’s likely to develop an allergy. That could mean screening before starting insulin, rather than waiting for a reaction to happen.

For now, the key is awareness. If you’ve had a strange reaction after an injection, don’t brush it off. Talk to your doctor. Get tested. Don’t assume it’s just a bad shot. Insulin is life-saving. You deserve to use it safely.

Can you outgrow an insulin allergy?

No, insulin allergies don’t typically go away on their own. Unlike some childhood food allergies, insulin reactions are usually persistent. But they can be managed effectively with switching insulin types, topical treatments, or desensitization. Even if you’ve had a reaction for years, treatment can still help you continue insulin safely.

Is insulin allergy more common with animal insulin?

Yes. Animal insulin-derived from pigs or cows-was responsible for up to 15% of allergic reactions in the 1930s and 1940s. Modern human insulin and insulin analogs are much purer and less likely to trigger immune responses. Today, less than 3% of users experience any kind of reaction, and most of those are mild and localized.

Can you be allergic to insulin pens but not vials?

It’s possible, but rare. Reactions to pens usually stem from the preservatives in the insulin itself, not the device. However, some people react to materials in the pen (like latex in seals or plastics), especially if they have contact dermatitis. If you suspect the pen, try switching from a pen to a vial and syringe-and vice versa-to see if the reaction changes.

Do antihistamines help with insulin allergies?

They help with immediate, IgE-mediated reactions-like hives or itching that shows up right after injection. But they don’t work for delayed reactions caused by T-cells, which appear hours later and involve bruising or joint pain. For those, you need topical immunosuppressants or corticosteroid creams, not antihistamines.

Can children develop insulin allergies?

Yes, though it’s rare. Children with type 1 diabetes can develop reactions to insulin, especially if they’ve been on animal insulin or older formulations. Parents should watch for persistent redness, swelling, or unexplained fussiness after injections. Early diagnosis is critical-children can’t communicate symptoms as clearly as adults, so caregivers need to be vigilant.

What’s the success rate of insulin desensitization?

Studies show that insulin desensitization completely resolves symptoms in about 67% of patients. Another 33% see significant improvement, meaning they can tolerate full doses without severe reactions. It’s not guaranteed, but it’s one of the most effective options for people who can’t switch insulin types or who need to stay on a specific insulin for medical reasons.

Can you test for insulin allergy before starting insulin?

Not routinely. There’s no standard pre-screening test for insulin allergy because it’s so rare. Testing is only done after a reaction occurs. Researchers are exploring blood biomarkers that might predict risk, but those aren’t available yet. For now, the best prevention is monitoring closely during the first few weeks of insulin therapy.

Does insulin allergy increase the risk of other allergies?

Having an insulin allergy doesn’t mean you’re more likely to develop allergies to other drugs or foods. But people with existing allergic conditions-like asthma, eczema, or hay fever-may be slightly more prone to insulin reactions. It’s not a direct link, but immune sensitivity plays a role. If you have a history of multiple allergies, tell your doctor before starting insulin.