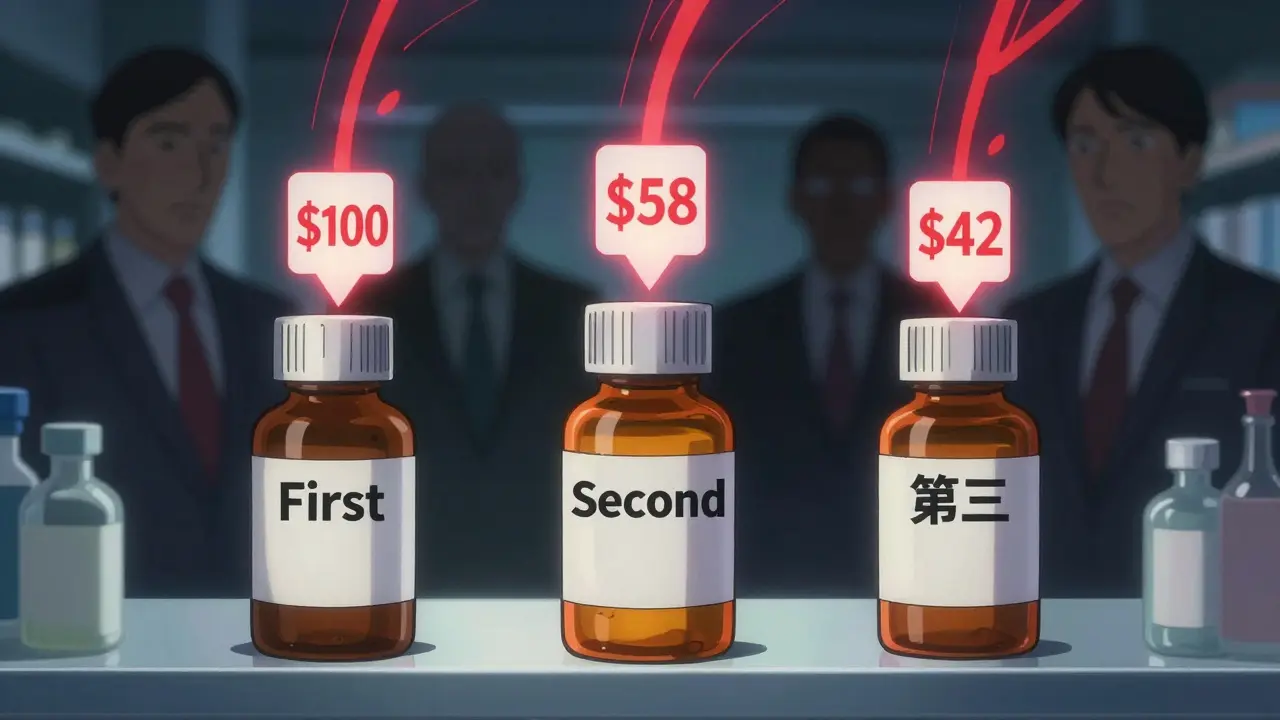

When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the first generic version usually hits the market at about 87% of the original price. That’s a big drop-but it’s just the beginning. The real savings come when a second and then a third generic manufacturer enters the race. This isn’t just theory. It’s what’s happening right now in pharmacies across the U.S., and it’s saving patients billions every year.

Why the second generic makes the biggest difference

The first generic drug to enter the market after a patent expires doesn’t drop prices to rock bottom. Why? Because there’s still no real competition. The single manufacturer has little pressure to lower prices further. But when a second company gets approval and starts selling the same drug, everything changes. Suddenly, two companies are fighting for the same customers. That drives prices down to about 58% of the original brand price. That’s a 36% drop from the first generic alone. This isn’t guesswork. The FDA analyzed over 1,000 generic drugs approved between 2018 and 2020. In markets with just one generic, prices hovered around 87% of the brand. Add a second, and prices plunged to 58%. The jump from one to two competitors didn’t just help-it was the single biggest price drop in the entire lifecycle of a generic drug.The third generic? Prices crash again

Now add a third manufacturer. This is where prices really collapse. With three companies competing, the average price falls to just 42% of the original brand cost. That’s more than half the price of the first generic. For a drug that used to cost $100 a month, you’re now paying $42. For patients on long-term medications-like blood pressure pills, statins, or diabetes drugs-that’s hundreds of dollars saved every year. The data doesn’t lie. A 2022 FDA report found that each additional generic entrant after the first cuts prices by another 20-30%. The effect isn’t linear-it’s explosive. The biggest savings happen between the first and third entrants. After that, prices keep falling, but the steepest drops are over by the time the third player joins the market.What happens when competition stalls

Here’s the scary part: nearly half of all generic drug markets never get past two manufacturers. These are called duopolies. And in duopolies, prices don’t just stop falling-they can actually rise. A 2017 study from the University of Florida tracked 300 generic drugs and found that when competition dropped from three companies to two, prices jumped 100% to 300% in some cases. Why? Because without a third player to pressure them, the two remaining manufacturers have less incentive to undercut each other. They may even coordinate prices silently. It’s not illegal-but it’s not competition either. This isn’t rare. The FDA says 47% of generic markets have only two competitors. That means nearly half of all patients aren’t getting the full benefit of price drops. They’re stuck paying more than they should because the market never reached the tipping point: three or more manufacturers.

Who’s behind the scenes? The supply chain squeeze

You’d think more generics = lower prices. But the system isn’t that simple. Behind the scenes, a handful of giant companies control how drugs move from factories to pharmacies. Three wholesalers-McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health-handle 85% of all generic drug distribution in the U.S. Three pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)-Express Scripts, CVS Health, and Optum-process 80% of prescriptions. These companies don’t just move pills. They negotiate discounts, set formularies, and decide which generics get shelf space. Here’s the problem: even when manufacturers slash prices, PBMs and wholesalers often keep most of the savings. A 2019 FDA analysis found that while manufacturer prices dropped 60-70% with multiple generics, what pharmacies actually paid only fell 40-50%. The rest? That’s the markup. And it’s not going to patients. This means the real savings aren’t always reflected in your co-pay. You might see a lower price on the shelf, but your insurance plan or pharmacy might still be paying more than they should. The benefit of competition is real-but it’s being filtered through a system that doesn’t always pass it along.How anti-competitive practices block savings

Brand-name drug companies don’t just wait for patents to expire. Some actively block generics from entering the market. One common trick? “Pay for delay.” A brand company pays a generic manufacturer to stay out of the market. In exchange for a cash payment, the generic company delays launching its version. The FDA estimates this costs patients $3 billion a year in higher out-of-pocket costs alone. In 2023, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association found these deals cost the entire system $12 billion annually. Another tactic? “Patent thicketing.” A brand company files dozens of overlapping patents-sometimes 70 or more-just to delay generics. One drug had 75 patents that stretched its monopoly from 2016 to 2034. That’s 18 extra years of high prices. These aren’t hypotheticals. They’re real, documented, and happening right now. The 2022 CREATES Act tried to stop some of this by forcing brand companies to share drug samples with generics. But enforcement is still patchy.

The 5 billion impact

Between 2018 and 2020, the FDA approved 2,400 new generic drugs. The total savings for patients? $265 billion. That’s not a typo. That’s over a quarter of a trillion dollars saved in just two years. The biggest chunk of that? From second and third generics. Each additional competitor added billions in savings. The ASPE (Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation) confirmed that markets with three or more generics saw price reductions of 70-80% compared to pre-generic levels. For chronic conditions, that means people aren’t skipping doses because they can’t afford their meds. This isn’t just about cost. It’s about access. Lower prices mean more people can stick to their treatment plans. Fewer hospitalizations. Fewer complications. That’s public health in action.What’s next? The future of generic competition

The trend is clear: more competitors = lower prices. But the number of independent generic manufacturers is shrinking. Teva bought Allergan’s generics. Viatris formed from the merger of Mylan and Upjohn. The market is consolidating. The FDA’s GDUFA III program (2023-2027) is trying to fix this by speeding up approvals for complex generics-like inhalers and injectables-where second and third entrants have been slow to appear. That’s good news. But it’s not enough. Without stronger enforcement against pay-for-delay deals and more support for new manufacturers, the system could stall. The Congressional Budget Office warns that without action, Medicare could lose $25 billion a year by 2030 because of blocked competition. The good news? The science is solid. The data is clear. And the solution is simple: more competition. Every time a second or third generic enters the market, patients win.Why do drug prices drop more after the third generic enters?

The first generic lowers prices from the brand level, but without competition, the price doesn’t fall much further. The second generic forces the first to cut prices to stay competitive. The third pushes both into a price war, often dropping costs to 40% or less of the original brand price. This is where the biggest savings happen-between the first and third entrant.

Can a drug have too many generics?

Not really. More generics usually mean lower prices. But if too many manufacturers enter a small market, some may exit because profits get too thin. This can lead to shortages or consolidation. The sweet spot is 3-5 competitors: enough to drive prices down, but not so many that companies can’t stay in business.

Why aren’t more second and third generics entering the market?

Several barriers exist. Brand companies use legal tactics like pay-for-delay deals and patent thickets to delay entry. Manufacturing complex generics (like inhalers or injectables) is expensive and hard to scale. And with only three major wholesalers and PBMs controlling most of the supply chain, new manufacturers have little negotiating power. Entry costs are high, and profits are squeezed.

Do lower generic prices mean lower quality?

No. The FDA requires all generics to meet the same strict standards as brand drugs. They must have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and bioequivalence. Lower prices come from lower marketing costs, no patent fees, and competition-not from cutting corners.

How can I tell if my drug has multiple generic options?

Check your pharmacy’s pricing sheet or ask your pharmacist. If your drug has multiple manufacturers listed on the bottle (like Teva, Mylan, or Sandoz), you have competition. You can also search the FDA’s Orange Book online to see how many approved generic versions exist for your medication. More entries usually mean better prices.