When the body can’t pull nutrients out of the food you eat, the fallout isn’t just tiredness or weight loss - it’s often a sign that something in the gut isn’t working right. Understanding why food malabsorption happens can help you spot hidden gut problems before they spiral.

Quick Takeaways

- Malabsorption occurs when the small intestine, enzymes, or gut bacteria fail to break down or absorb nutrients.

- Inflammatory conditions like celiac disease and Crohn’s disease are top culprits.

- Non‑inflammatory issues such as lactose intolerance or pancreatic insufficiency can also cause poor absorption.

- Symptoms range from chronic diarrhea and bloating to unexplained anemia or bone loss.

- Accurate diagnosis combines blood tests, stool analysis, breath tests, and sometimes endoscopy.

Understanding Food Malabsorption

Malabsorption is a condition where the gastrointestinal (GI) tract fails to properly absorb nutrients, vitamins, and minerals from ingested food. It can affect macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, fats) and micronutrients (iron, calcium, B12). When absorption drops below a functional threshold, the body shows clinical signs like weight loss, fatigue, and nutrient deficiencies.

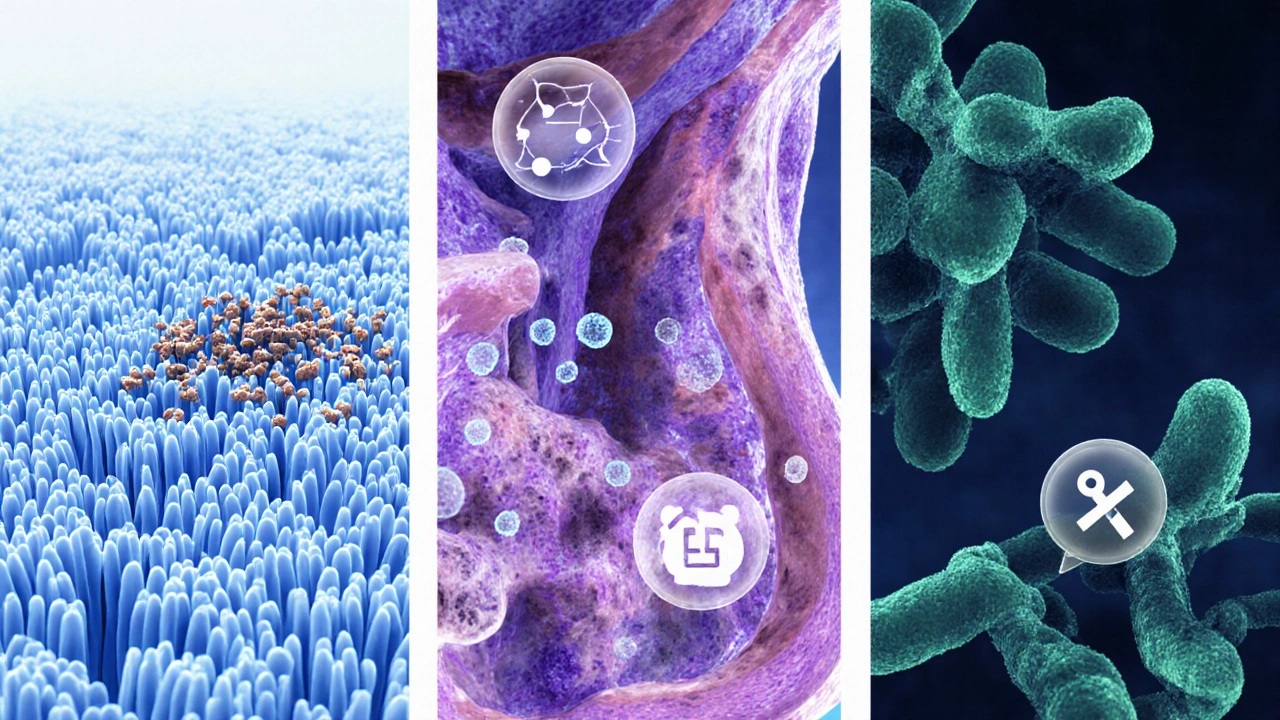

The small intestine does most of the heavy lifting. Its inner lining, covered in finger‑like villi, increases surface area for absorption. Enzymes from the pancreas and brush‑border cells break down complex molecules, while a balanced gut microbiome fine‑tunes the process.

How GI Disorders Trigger Malabsorption

Gastrointestinal disorders disrupt one or more steps in the absorption chain:

- Structural damage - Inflammatory diseases erode villi, shortening the absorptive surface.

- Enzyme deficiency - Pancreatic or brush‑border enzymes may be missing or inactive, leaving nutrients undigested.

- Microbial imbalance - Overgrowth of harmful bacteria competes for nutrients and produces metabolites that impair transport proteins.

- Transport defects - Certain genetic conditions affect specific transporters, but they’re rare compared with acquired disorders.

Below, each major GI condition is broken down by the exact way it hampers absorption.

Common GI Disorders Linked to Malabsorption

These are the most frequently seen disorders that directly or indirectly cause nutrient loss.

Celiac disease is an autoimmune reaction to gluten that damages the lining of the small intestine. The immune attack flattens villi, reducing surface area and blocking iron, calcium, and folate absorption.

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that can affect any part of the GI tract, but when it involves the ileum, bile‑acid reabsorption is impaired, leading to fat malabsorption and deficiency of fat‑soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K).

Lactose intolerance stems from lactase enzyme deficiency. Undigested lactose draws water into the colon, causing diarrhea and preventing calcium uptake.

Pancreatic insufficiency occurs when the pancreas can’t release enough digestive enzymes such as lipase and amylase. This leads to fatty stools (steatorrhea) and loss of vitamins A, D, E, K.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is an excessive growth of bacteria in the small intestine that competes for nutrients, deconjugates bile acids, and damages the mucosa, resulting in B‑vitamin and iron deficiencies.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) isn’t inflammatory, but chronic motility changes can speed transit time, giving the intestine less time to absorb nutrients, especially water‑soluble vitamins.

| Disorder | Primary Mechanism | Typical Deficiencies | Diagnostic Clue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Celiac disease | Villous atrophy due to gluten‑triggered autoimmunity | Iron, calcium, folate, vitamin D | Positive anti‑tTG IgA, duodenal biopsy |

| Crohn’s disease (ileal involvement) | Inflammation + bile‑acid loss | Vitamin B12, fat‑soluble vitamins | Elevated fecal calprotectin, imaging |

| Lactose intolerance | Lactase deficiency | Calcium, riboflavin | Hydrogen breath test |

| Pancreatic insufficiency | Enzyme shortage | Fat‑soluble vitamins, protein | Fecal elastase <10µg/g |

| SIBO | Bacterial competition & bile‑acid deconjugation | Vitamin B12, iron | Glucose or lactulose breath test |

| IBS | Rapid transit & altered motility | Magnesium, water‑soluble vitamins | Rome IV criteria, normal labs |

Signs and Symptoms to Watch

Because malabsorption can affect many nutrients, symptoms are often vague. Keep an eye out for the following patterns:

- Chronic loose stools or greasy, foul‑smelling stool (steatorrhea).

- Unexplained weight loss despite normal or increased calorie intake.

- Persistent anemia that doesn’t improve with oral iron.

- Bone pain or frequent fractures - a hint of calcium or vitamin D loss.

- Neurological tingling, balance issues, or memory fog - signals of B‑vitamin deficiency.

- Frequent mouth ulcers or glossitis - often linked to folate or iron shortage.

If you notice a cluster of two or more of these signs, it’s worth talking to a healthcare professional about malabsorption testing.

Diagnosing Malabsorption

Doctors use a step‑wise approach, starting with the least invasive tests.

- Blood panels - Complete blood count, ferritin, vitamin D, B12, folate, and electrolyte levels give a snapshot of nutrient status.

- Stool analysis - Checks for fat content (90mg/day cutoff) and looks for parasites or occult blood.

- Breath tests - Hydrogen or methane breath after lactulose or glucose ingestion detects SIBO and lactose intolerance.

- Fecal elastase - Low levels (<200µg/g) point to pancreatic insufficiency.

- Imaging & endoscopy - Upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies confirms celiac disease; CT or MR enterography visualizes Crohn’s lesions.

Combining these results helps pinpoint whether the problem is structural, enzymatic, microbial, or a mix.

Managing and Treating Underlying GI Disorders

Treatment always starts with the root cause. Below are the most common strategies, broken down by disorder.

- Celiac disease - Strict gluten‑free diet eliminates the trigger, allowing villi to regenerate within months. Nutrient supplementation (iron, calcium, vitamin D) is often needed during recovery.

- Crohn’s disease - Anti‑inflammatory meds (corticoids, biologics like infliximab) reduce mucosal damage. When the ileum heals, bile‑acid sequestrants can be tapered.

- Lactose intolerance - Lactase enzyme tablets taken before dairy or a low‑lactose diet. Calcium‑rich alternatives (almond or fortified soy milk) keep bone health on track.

- Pancreatic insufficiency - Pancrelipase enzyme replacement (usually 25,000-40,000lipase units per meal) improves fat digestion. Monitoring stool fat after starting therapy helps fine‑tune the dose.

- SIBO - A short course of antibiotics (rifaximin 550mg TID for 14days) reduces bacterial load, followed by a low‑FODMAP diet to prevent relapse.

- IBS - Fiber modulation, peppermint oil capsules, and stress‑reduction techniques (biofeedback, CBT) can normalize transit time, indirectly improving absorption.

Supplements should be taken under supervision, as excess iron or vitamin A can be harmful.

Lifestyle Tips to Boost Nutrient Absorption

Even after the medical issue is addressed, everyday habits can keep your gut efficient.

- Chew food thoroughly - digestion begins in the mouth; proper breakdown eases the work of enzymes downstream.

- Avoid drinking large amounts of water with meals - it dilutes stomach acid and can slow nutrient breakdown.

- Include probiotic‑rich foods (yogurt, kefir, fermented vegetables) to maintain a healthy microbiome.

- Schedule regular, balanced meals - erratic eating can stress the gut’s motility patterns.

- Limit alcohol and NSAIDs - both damage the intestinal lining over time.

- Stay active - gentle exercise stimulates gut motility and improves blood flow to the intestinal wall.

Small tweaks add up, especially for people recovering from an acute GI flare.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can food malabsorption happen without a diagnosed GI disease?

Yes. Temporary factors like a viral gastroenteritis, high‑stress periods, or certain medications (e.g., metformin) can disrupt enzyme production or gut flora, leading to short‑term malabsorption. Most cases resolve once the trigger is removed.

How long does it take for villi to recover after starting a gluten‑free diet?

In most adults, noticeable improvement occurs within 3‑6 months, and complete histological healing can take up to 2years. Children often heal faster, sometimes within weeks.

Should I take a multivitamin if I have IBS?

A generic multivitamin can help fill minor gaps, but it’s better to test specific levels first. Targeted supplements (e.g., magnesium citrate or a B‑complex) often address the exact deficiencies seen in IBS.

Is a breath test reliable for detecting SIBO?

Breath tests are useful screening tools but can produce false‑negatives if the bacterial population is low‑hydrogen producing. Combining the breath test with symptoms and, if needed, a trial of antibiotics offers a more accurate picture.

Can over‑the‑counter enzymes fix my malabsorption?

Enzyme supplements work only when the deficiency matches the product. For example, lactase tablets help with lactose intolerance, while pancreatic enzymes target fat malabsorption. Using the wrong enzyme won’t improve absorption and may cause side effects.