Chronic heartburn isn’t just annoying-it’s a warning sign. If you’ve had acid reflux for more than 10 years, especially if it happens several times a week, your esophagus may be changing in ways you can’t see. That change is called Barrett’s esophagus, and it’s the body’s attempt to heal itself after years of stomach acid burning the lining. But this repair comes with a dangerous catch: it increases your risk of esophageal cancer.

What Exactly Is Barrett’s Esophagus?

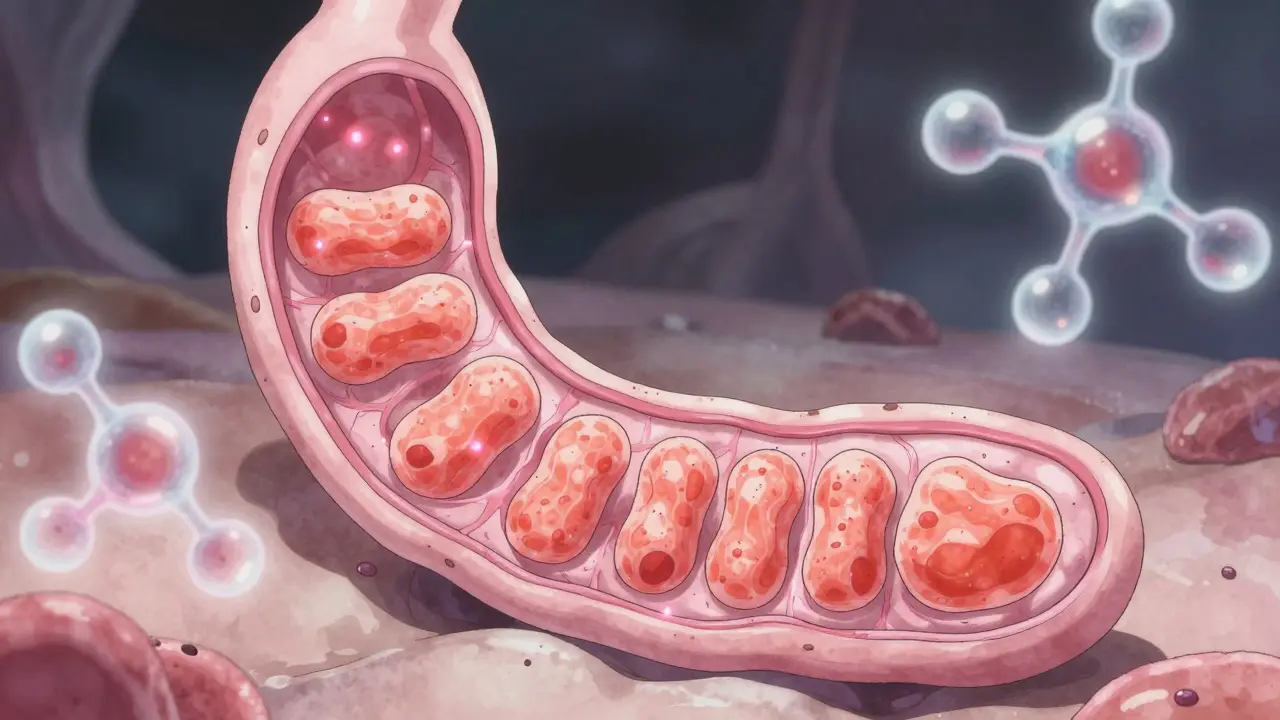

Barrett’s esophagus happens when the normal pink, flat cells lining your esophagus get replaced by thick, red, column-shaped cells that look more like the lining of your intestine. This is called intestinal metaplasia. It’s not cancer, but it’s the closest thing to a warning siren before cancer develops. The condition was first identified in 1950 by British pathologist Norman Barrett, and since then, we’ve learned it’s not rare-about 5.6% of people in the U.S. have it. Among those with long-term GERD, that number jumps to 10-15%.

The process takes time. It usually needs at least 10 years of regular acid exposure before the cells start to change. And it’s not random. Men are three times more likely to develop it than women. White men over 50 with a history of smoking or obesity are at the highest risk. If you’ve had heartburn more than three times a week for over 20 years, your risk of esophageal cancer is 40 times higher than someone without GERD.

Why You Can’t Rely on Symptoms

Here’s the tricky part: Barrett’s esophagus doesn’t cause new symptoms. You won’t suddenly feel different. You’ll still have the same heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, or trouble swallowing you’ve had for years. That’s why so many people don’t realize they have it-until it’s too late. The Esophageal Cancer Action Network found that 68% of people with Barrett’s esophagus had symptoms for over five years before being diagnosed. They thought it was just "bad indigestion."

That’s why screening isn’t optional for high-risk groups. If you’re a man over 50 with chronic GERD, you need to talk to a doctor-even if your heartburn is under control with medication. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole can stop the burning feeling, but they don’t always stop the acid from damaging your esophagus. Studies show that even with daily PPI use, 30-45% of patients still have acid reflux at night. Symptom relief doesn’t equal tissue protection.

How Barrett’s Esophagus Is Diagnosed

The only way to know for sure is through an upper endoscopy. A thin, flexible tube with a camera is passed down your throat to look at the esophagus. If the lining looks abnormal-salmon-colored instead of pale pink-biopsies are taken. The standard method is the Seattle protocol: four tissue samples are taken every 1 to 2 centimeters along the affected area. That’s usually 12 to 24 samples total. Why so many? Because cancer doesn’t grow evenly. It starts in tiny spots. Missing even one can mean missing early cancer.

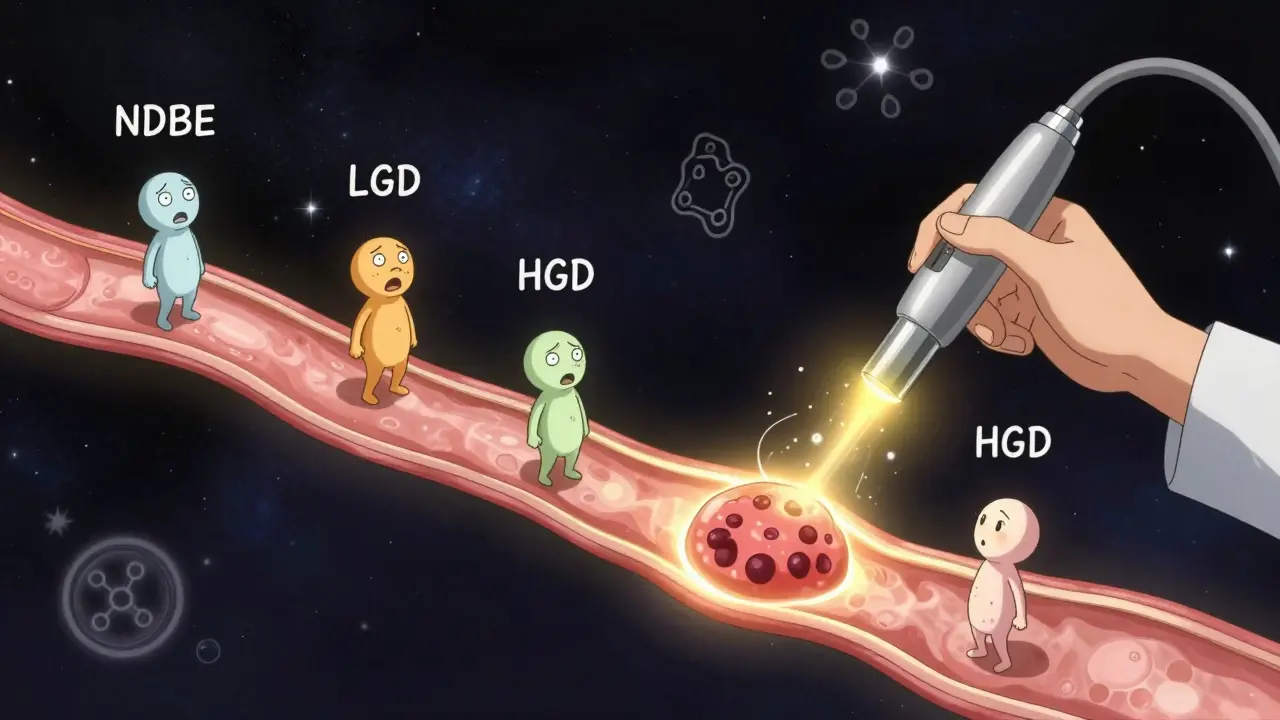

Pathologists then check the tissue for dysplasia-abnormal cell changes. There are four stages:

- Non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (NDBE): No abnormal cells. This is the most common finding.

- Indefinite for dysplasia: The cells look odd, but it’s not clear if they’re pre-cancerous.

- Low-grade dysplasia (LGD): Mild cell changes. Risk of cancer is low but real.

- High-grade dysplasia (HGD): Severe cell changes. This is the last step before cancer. About 6-19% of people with HGD develop cancer each year.

It’s not just about the diagnosis-it’s about getting it right. A 2022 study found that pathologists disagreed on dysplasia readings in nearly 25% of cases. That’s why guidelines now recommend that LGD be confirmed by a second expert pathologist before deciding on treatment.

Who Should Be Screened?

Not everyone with heartburn needs an endoscopy. Screening is targeted. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends it for:

- Men over 50

- With chronic GERD (symptoms for more than 5 years)

- Who have symptoms at least once a week

- And at least one additional risk factor: white race, smoking, obesity (BMI over 30), or a family history of esophageal cancer

Women and younger men without extra risk factors are generally not screened. Why? Because the overall risk is too low to justify the cost and potential risks of repeated procedures. But if you’re in the high-risk group, don’t wait. A 2022 analysis showed that men in this group account for 79% of all Barrett’s diagnoses-even though they’re only half the population.

What Happens After Diagnosis?

If you’re diagnosed with non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, you’ll need an endoscopy every 3 to 5 years. That’s it. No treatment needed-just monitoring. For low-grade dysplasia, the guidelines changed in 2022. Now, most patients are offered endoscopic therapy, not just surveillance. Why? Because a five-year follow-up study (AIMS-2 trial) showed that 94% of patients who got treatment never had dysplasia return.

The go-to treatment is radiofrequency ablation (RFA). It uses heat to destroy the abnormal tissue. In clinical trials, RFA cleared dysplasia in 90-98% of cases. Cryotherapy, which freezes the tissue, is another option. Both are done during endoscopy. Most patients go home the same day. Recovery is quick. And the results are lasting: 80% of people who clear dysplasia remain cancer-free after five years.

High-grade dysplasia is treated the same way-no waiting. It’s not a "watch and wait" situation anymore. The risk is too high.

Lifestyle Changes That Actually Help

Medication alone isn’t enough. You need to change your habits. Here’s what works, backed by data:

- Stop eating 3 hours before bed-gravity helps keep acid down.

- Elevate the head of your bed by 6-8 inches. Use blocks or a wedge, not just extra pillows.

- Loosen your waistband. Belly fat pushes stomach contents up.

- Avoid triggers: fatty foods, chocolate, caffeine, alcohol, spicy meals, and mint.

- Quit smoking. Smoking weakens the lower esophageal sphincter and reduces healing.

- Get your BMI under 25. Losing even 10 pounds can cut reflux episodes in half.

These aren’t suggestions-they’re medical interventions. A 2021 study showed that patients who combined lifestyle changes with high-dose PPIs had significantly less acid exposure than those on medication alone.

The Future: Less Endoscopy, More Precision

Right now, 95% of people with Barrett’s esophagus will never get cancer. But they still get endoscopies every few years. That’s expensive, uncomfortable, and sometimes risky. New tools are changing that.

The TissueCypher Barrett’s Esophagus Assay is a blood and tissue test that analyzes molecular markers to predict cancer risk. It got Medicare coverage in 2021 after a study showed a 96% accuracy rate in ruling out progression to high-grade dysplasia or cancer. That means some patients might skip endoscopies for years if their test shows low risk.

Another promising area is DNA methylation testing. Researchers in Texas are testing a panel of genetic markers that could identify the 5% of Barrett’s patients who will actually develop cancer. If it works, we could cut unnecessary endoscopies by 40%.

What to Do Next

If you’ve had chronic GERD for over 10 years, especially if you’re a man over 50, talk to your doctor. Don’t wait for worse symptoms. Don’t assume your PPIs are protecting you. Ask: "Do I need an endoscopy to check for Barrett’s esophagus?"

If you’ve already been diagnosed, follow your surveillance schedule. Don’t skip appointments. If you have dysplasia, ask about ablation. It’s not a cure, but it’s the best way to prevent cancer.

And if you’re tired of heartburn-really tired-start changing your habits. Losing weight, stopping smoking, and avoiding late-night meals aren’t just about comfort. They’re about survival.

Can Barrett’s esophagus go away on its own?

No, Barrett’s esophagus doesn’t reverse itself without treatment. The abnormal cells stay unless they’re removed. But with endoscopic therapies like radiofrequency ablation, the abnormal tissue can be destroyed and replaced with normal lining. Studies show that up to 90% of patients achieve complete eradication of Barrett’s tissue after treatment.

Does taking PPIs prevent cancer in Barrett’s esophagus?

PPIs help control symptoms and reduce acid exposure, but they don’t guarantee cancer prevention. Studies have not proven that PPIs alone lower the risk of esophageal cancer in people with Barrett’s esophagus. Complete acid suppression is important, but lifestyle changes and regular surveillance are still essential. Some patients still have acid reflux even on high-dose PPIs.

Is Barrett’s esophagus hereditary?

There’s no single gene that causes Barrett’s esophagus, but family history matters. People with a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, child) who had Barrett’s or esophageal cancer have a higher risk. This suggests shared genetics, lifestyle, or environmental factors play a role. If you have a family history, discuss earlier screening with your doctor.

Can I still eat normally if I have Barrett’s esophagus?

You don’t have to give up food entirely, but you need to be smart. Avoid known triggers like fatty meals, chocolate, caffeine, alcohol, and spicy foods. Eat smaller portions and never lie down right after eating. Many people find that once they adjust, they feel better than before-less bloating, less pain, and better sleep. It’s not a diet; it’s a long-term health strategy.

How often should I get an endoscopy if I have Barrett’s esophagus?

It depends on your dysplasia level. For non-dysplastic Barrett’s, every 3 to 5 years. For low-grade dysplasia, confirm with an expert, then repeat endoscopy in 6 to 12 months. If dysplasia is gone, return to 3-year intervals. For high-grade dysplasia, endoscopic treatment is recommended instead of surveillance. Always follow your doctor’s plan-guidelines vary slightly by region and institution.

Are there alternatives to endoscopy for screening?

Yes, but they’re not replacements yet. The TissueCypher test is a promising blood and biopsy-based tool that assesses cancer risk without needing repeated endoscopies. It’s covered by Medicare for certain patients. Other tests, like swallowable capsule endoscopes, are being tested but aren’t standard. Endoscopy is still the gold standard for diagnosis and monitoring.