Pregnancy AF Management Tool

Personalize Your Treatment Plan

Enter your pregnancy details to get safe treatment recommendations for atrial fibrillation management.

Treatment Recommendations

Results will appear here after calculation

When a pregnant woman develops Atrial Fibrillation, the stakes feel higher for both her and the baby. The heartbeat’s irregular rhythm can trigger complications that ripple through the entire pregnancy journey. This guide walks you through what the condition looks like during pregnancy, which dangers to watch for, and how clinicians balance maternal safety with fetal health.

What is Atrial Fibrillation and Why Does It Matter in Pregnancy?

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, defined by chaotic electrical activity in the atria that leads to an irregular, often rapid heart rate. In non‑pregnant adults, AF can cause palpitations, fatigue, and an increased risk of stroke. During pregnancy, the physiological changes-higher blood volume, increased cardiac output, and hormonal shifts-can both trigger new‑onset AF and worsen existing disease.

Understanding how AF behaves in a pregnant body is essential because the condition can influence maternal mortality, fetal growth, and decisions about labor and delivery.

Maternal Risks: What Can Go Wrong?

Pregnant people with AF face several specific hazards:

- Thromboembolic events: The chaotic atrial rhythm promotes clot formation, raising the chance of stroke or peripheral embolism.

- Heart failure: The added cardiac workload of pregnancy can tip an already strained heart into decompensation.

- Arrhythmia‑related syncope: Sudden drops in blood pressure may cause fainting, increasing fall risk.

- Maternal mortality: Though rare, severe AF‑related complications can be fatal.

These risks demand vigilant monitoring and a clear treatment plan tailored to the trimester and the woman’s overall health.

Fetal Risks: How the Baby Is Affected

The fetus isn’t directly experiencing the irregular heartbeat, but maternal AF can indirectly affect development:

- Reduced placental perfusion if the mother’s cardiac output falls.

- Potential exposure to anticoagulant drugs that cross the placenta.

- Preterm birth if severe maternal instability leads clinicians to deliver early.

Most babies born to mothers with well‑controlled AF have normal outcomes, but early detection and safe medication choices are crucial.

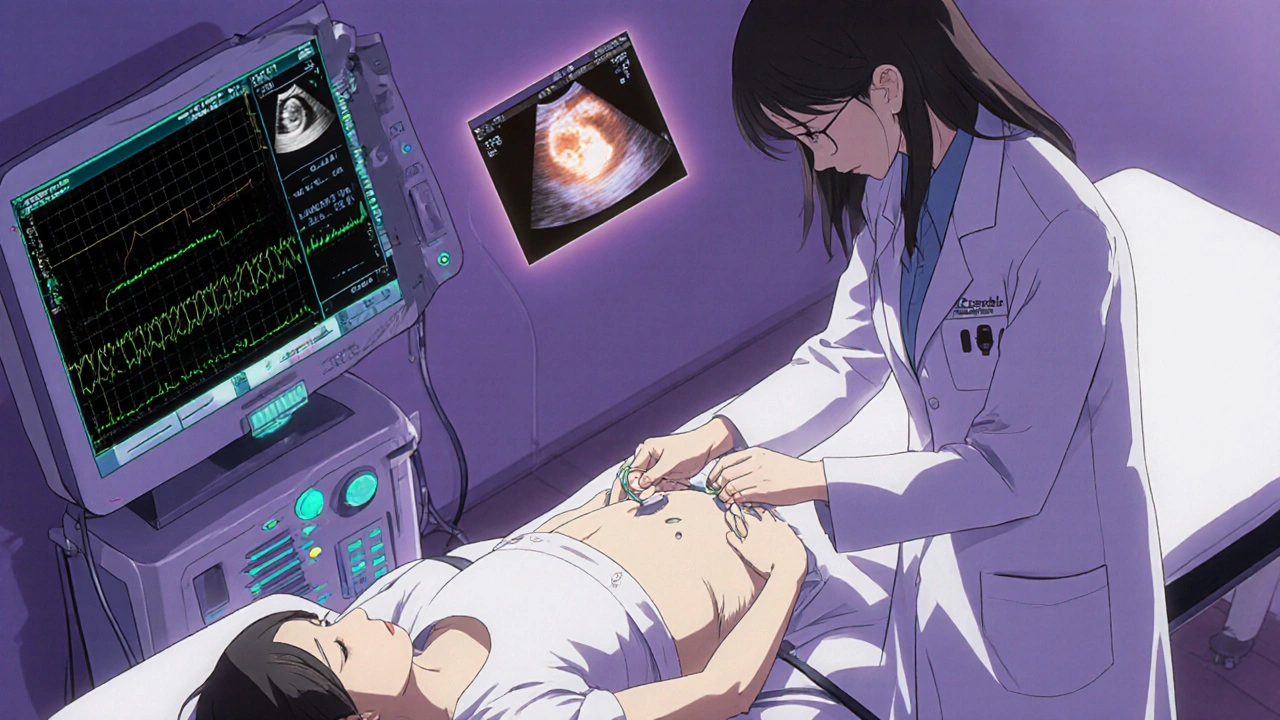

Diagnosing AF in Pregnancy

Diagnosis follows the same principles as in the general population, but with extra caution to limit radiation exposure:

- Clinical assessment: Palpitations, dyspnea, or irregular pulse prompt an ECG.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): A simple 12‑lead ECG is safe and confirms AF.

- Echocardiography: Checks for structural heart disease, left‑atrial size, and ventricular function without radiation.

- Holter monitoring: Provides 24‑48 hour rhythm data if episodes are intermittent.

Blood work-thyroid function, electrolytes, and coagulation profile-helps uncover reversible triggers.

Management Strategies: Balancing Safety and Efficacy

Managing AF in pregnancy revolves around three pillars: rate control, rhythm control, and anticoagulation. The choice depends on symptom severity, gestational age, and underlying heart disease.

Rate Control

Keeping the ventricular rate below 100 bpm is often enough for mild symptoms. Preferred agents include:

| Drug | Class | Pregnancy Category | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metoprolol | Beta‑blocker | Category C | Most data support safety; watch for fetal growth restriction. |

| Labetalol | Alpha/Beta‑blocker | Category C | Often used for hypertension; also controls rate. |

| Digoxin | Cardiac glycoside | Category C | Limited placental transfer; useful when beta‑blockers intolerable. |

Calcium‑channel blockers like diltiazem are options in the second trimester but require careful blood‑pressure monitoring.

Rhythm Control

Restoring sinus rhythm may be necessary for hemodynamic instability or when rate control fails. Options include:

- Cardioversion: Electrical cardioversion is considered safe at any gestational age when sedation is minimized.

- Anti‑arrhythmic drugs: Class IC agents (flecainide, propafenone) are generally avoided; class III drugs (sotalol, amiodarone) have limited data and are reserved for refractory cases.

- Catheter Ablation: Typically postponed until after delivery, but can be performed in the third trimester if life‑threatening arrhythmia persists.

Anticoagulation: Preventing Clots Without Harming the Baby

Because AF raises stroke risk, anticoagulation is often indicated. The challenge is finding a drug that protects the mother while staying safe for the fetus.

| Drug | Category | Placental Transfer | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin | Vitamin K antagonist | High | Avoid in 1st trimester and near delivery; use only if benefits outweigh risks. |

| Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) | Heparin | None | Preferred in 1st trimester; requires IV infusion and aPTT monitoring. |

| Low‑Molecular‑Weight Heparin (LMWH) | Heparin | None | Standard of care in 2nd/3rd trimesters; once‑daily dosing. |

Guidelines suggest maintaining a target anti‑Xa level of 0.5-1.0 IU/mL for LMWH in pregnant AF patients.

Delivery Planning and Intrapartum Care

Deciding when and how to deliver hinges on maternal rhythm stability and anticoagulation status:

- Vaginal delivery is feasible for most women with controlled AF and therapeutic LMWH stopped 24 hours before labor.

- Cesarean section may be preferred if rapid delivery is needed due to hemodynamic compromise.

- Continuous cardiac monitoring during labor helps catch breakthrough tachyarrhythmias.

- Regional anesthesia is safe once anticoagulation is paused per guidelines.

Post‑delivery, anticoagulation resumes promptly, usually within 12 hours after vaginal birth or 24 hours after a C‑section, to limit postpartum clot risk.

Postpartum Management

The first six weeks after birth are a high‑risk window. Hormonal shifts can trigger AF recurrences, so a follow‑up plan is essential:

- Re‑evaluate rate‑control meds; some beta‑blockers may be tapered if blood pressure normalizes.

- Continue LMWH for at least six weeks if the CHA₂DS₂‑VASc score (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke history, vascular disease, sex) warrants it.

- Consider transitioning to long‑term oral anticoagulants (e.g., apixaban) once breastfeeding safety is confirmed.

- Encourage gradual return to exercise; low‑impact activities improve autonomic tone without overloading the heart.

Lifestyle Adjustments During Pregnancy

Even with medication, lifestyle plays a big role in keeping AF in check:

- Stay hydrated; dehydration can precipitate arrhythmias.

- Limit caffeine and avoid stimulants like decongestants.

- Maintain a balanced diet rich in omega‑3 fatty acids, which may have modest anti‑arrhythmic effects.

- Practice stress‑relief techniques-prenatal yoga, breathing exercises, and short walks.

- Track heart rate daily with a wearable or manual pulse check; report any sustained >110 bpm to your cardiologist.

These habits not only help control AF but also support overall pregnancy health.

Key Takeaways

Here’s a quick snapshot of what you need to remember:

- Atrial fibrillation is manageable in pregnancy with proper monitoring.

- Maternal risks include stroke, heart failure, and syncope; fetal risks center on preterm birth and medication exposure.

- Rate control with beta‑blockers or digoxin is first‑line; rhythm control or cardioversion is reserved for instability.

- LMWH is the anticoagulant of choice; warfarin is avoided except in rare, high‑risk scenarios.

- Delivery plans should coordinate timing of anticoagulation pauses, and postpartum follow‑up is critical.

Can I have a natural birth if I have atrial fibrillation?

Yes, most women with well‑controlled AF can attempt a vaginal delivery. The key is to stop LMWH 24 hours before labor, monitor the heart rhythm continuously, and have a plan for rapid cardioversion if needed.

Is warfarin ever safe during pregnancy?

Warfarin crosses the placenta and can cause fetal warfarin syndrome, especially in the first trimester. It may be considered in the third trimester only if the mother's clot risk is extremely high and no alternative exists, and even then it’s stopped before delivery.

How often should I see my cardiologist during pregnancy?

At least once each trimester, plus an extra visit if you notice new palpitations, shortness of breath, or any side effects from medication.

Can beta‑blockers affect my baby’s growth?

Some studies show a slight increase in small‑for‑gestational‑age infants with high‑dose beta‑blockers, but the benefit of preventing maternal complications usually outweighs the risk. Your doctor will use the lowest effective dose.

When can I stop anticoagulation after delivery?

If you remain at high stroke risk (CHA₂DS₂‑VASc ≥2), continue anticoagulation for at least six weeks postpartum. After that, discuss long‑term options with your cardiologist.